THE APOSTLE ST. JAMES

James, son of the fisherman Zebedee, was one of the 12 apostles, as was his brother John the Evangelist. After Christ’s resurrection, he travelled around the Iberian Peninsula for many years, evangelising. Returning to Palestine in 43/44, he was beheaded by King Herod Agrippa, who feared that the apostle was gaining too much power; his disciples, Attanasio and Theodore, collected his body and secretly transported it by ship to the places where he was preaching. They disembarked at Finisterre, went to Galicia and buried him. In the centuries that followed, traces of the tomb were lost. In 813, the hermit Pelayo saw a shower of stars falling over a hill for several days. One night, Saint James appeared to him in a dream and told him that the location of the lights pointed to his tomb. The abbot removed the earth that had settled over the centuries and discovered the tomb. He took the news to the local bishop, Teodomiro, who confirmed the authenticity of the event. The news soon reached the Pope and the most important Catholic rulers of the time. Thus began the cult of Santiago (the name is a contraction of Saint James).

A small church was built on the site of the tomb and soon a town grew up around it, which was named Santiago de Compostela (from campus stellae). Another etymological study claims that the term comes from the Latin Compostum (cemetery), due to the discovery of a necropolis dating from the 1st century BC during archaeological excavations in Compostela between 1953 and 1959.

PILGRIMAGES

On departure, the pilgrim stripped himself of his possessions and often had to sell or mortgage them to finance his journey. He would draw up a will and make arrangement for the administration of his property in his absence. The Church often intervened actively in this guardianship function. This special status gave the pilgrim special prestige. The decision to go on a pilgrimage was generally a free personal choice:

– to ask for a grace

– to fulfil a vow

– for a personal religious quest

In many cases, however, it was imposed as a punishment by the judge or as penance by the confessor for particularly serious faults or sins. Those who were rich could send a person on a pilgrimage at their own expense. Pilgrims usually travelled in groups to support and protect each other: the dangers were the often the precarious state of the roads, natural disasters and, above all, the bandits who plagued the roads.

A network of services for pilgrims developed along the route: churches, monasteries, lodgings, hospices, hospitals, inns, many of which can still be seen today. Villages and towns sprang up along the way, and roads and bridges were built. For a long time, the pilgrims were protected from robbers by various knightly orders, the most important of which were the Knights Templar (until their suppression in the 13th century). Many kings and famous personalities made the pilgrimage: Saint Francis was one of them.

On departure, the rite of dressing was performed with the handing over of the saddlebag:

Accipe hanc peram habitum peregrinationis tuae ut bene castigatus et emendatus pervenire merearis ad limina sancti Iacobi, quo pergere cupis, et peracto itinere tuo ad nos incolumis con gaudio revertaris, ipso praestante qui vivit et regnat Deus in omnia saecula saeculorum

And the cane:

Take this saddlebag, which will be the garment of your pilgrimage, so that you may be worthy to arrive at the gate of St James, where you wish to go, dressed in the best of clothes, and, having completed your journey, return to us safely and with great joy, if it pleases God, who lives and reigns for ever and ever.

Accipe hunc baculum, sustentacionem itineris ac laboris ad viam peregrinationis tuae ut devincere valeas omnes catervas inimici et pervenire securus ad limina sancti Iacobi et peracto cursu tuo ad nos revertaris cum gaudio, ipso annuente qui vivit et regnat Deus in omnia saecula saeculorum

Receive this cane to sustain you on your journey and your fatigue on the way of your pilgrimage, so that it may serve you to strike down anyone who would harm you, and so that you may arrive safely at the gate of St. James, and having completed your journey, return to us with great joy, under the protection of God, who lives and reigns forever and ever.

The pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela

For several centuries, the Arabs had settled and dominated southern and central Spain: Saint James became the symbol and protector of the Reconquista, the process by which the Spanish princes reclaimed the part of the peninsula occupied by the Moors. Saint James was therefore portrayed as a warrior saint (and called Matamoro = slayer of the Moors). It is said that the saint intervened several times to help the Christians defeat the Moors in the many battles fought over the following centuries (the Reconquista was completed in 1492 with the final defeat of the Arabs by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella ‘the Catholic’). Pilgrimages began immediately after the discovery of the tomb. Pilgrims from all over Europe gathered there: the Milky Way indicated the direction to follow. The flow became massive at certain times.

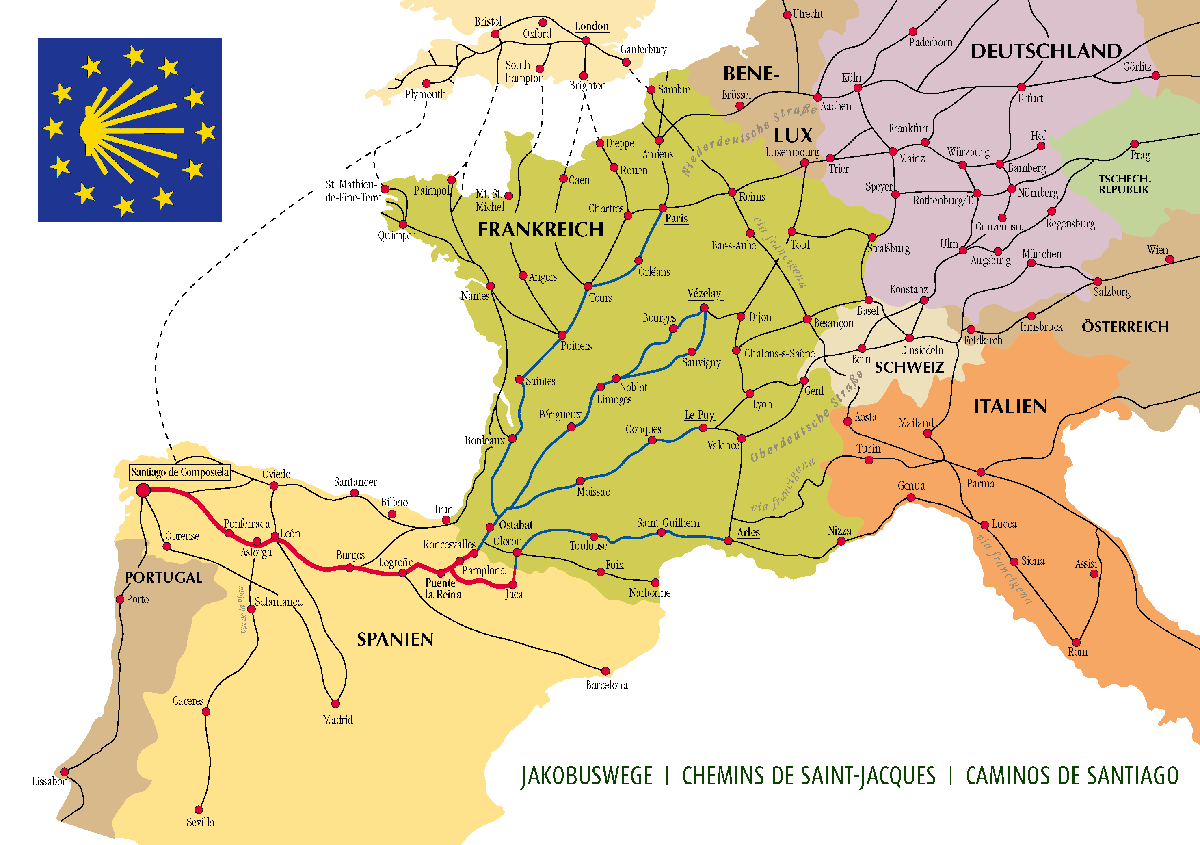

The major pilgrimage routes

The pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela spread rapidly throughout the Christian world as part of the revival of spirituality that marked the beginning of the second millennium. Dante Alighieri (Vita Nova, XL, XXIV) speaks of three great pilgrimage routes

– the one directly to Jerusalem – the pilgrims were called “palmieri” – from the palm tree -that was also the symbol of their pilgrimage.

– the one to Rome – the pilgrims were called ‘romei’ (from Rome) and their symbol was the cross.

– the one to Santiago – they were the proper ‘pilgrims’ (to the farthest, most travelled place); their symbol was the scallop shell.

In fact, the three great pilgrimage routes of the Christian world consisted of:

– a series of routes coming from continental and insular Europe, which crossed what is now France along several paths, converging at Roncesvalles and Puente la Reina and heading towards Santiago de Compostela

– Another series of routes, coming from various European locations, joined the Via Francigena to Rome.

– Those going to the Holy Land followed the ancient Via Appia to the ports of Apulia. The same route was used in the opposite direction by pilgrims leaving Italy for Santiago, who crossed the Alps and joined the Via Tolosana.

Decadence and rebirth

The pilgrimage to Santiago experienced periods of higher or lower participation. It was mainly supported and promoted by the most enlightened and evangelical component of the Church.

From the 14th century onwards, the pilgrimage to Santiago declined due to the numerous wars that ravaged Europe and various disasters (especially the Black Death). The real decline began after the Protestant Reformation and the religious wars. The negative period continued throughout the first half of the 19th century, also due to the Age of Enlightenment and the French Revolution. The pilgrimage was revived in 1884 when the remains of St James, hidden for some 300 years, were brought to light. In the 20th century, the two World Wars and the Spanish Civil War led to a new decline. The Holy Year of 1948 marked its rebirth, while in the 1950s and 1960s numerous cultural and religious associations dedicated to the promotion and rediscovery of the Jacobean Route were set up.

The actual revival began in the 1980s. Pope John Paul II’s visit to Santiago in 1989, in connection with the World Youth Day, was a decisive factor: half a million young people from all over the world came to Santiago, the largest concentration of pilgrims ever recorded. Since then, the flow of pilgrims has increased progressively and inexorably.

Special mention should be made of Elias Valiña Sampedro, parish priest of O’Cebreiro and a great connoisseur of the Pilgrim’s Way to Compostela, to whom we owe the economic and cultural development of this part of the region of Lugo along which the Pilgrim’s Way runs. As well as being one of the first to welcome pilgrims to the palloza10 in which he lived, at the end of the 1970s he began to mark the entire route of the Pilgrim’s Way with flechas amarillas – arrows of waterproof yellow paint. As a result of his tireless work, which included recovering the original sections of the Jacobean route that had been lost, he was appointed coordinator of the Pilgrim’s Way at the I Encuentro Jacobeo (Jacobean Meeting) in 1985. He also began publishing the Boletín del Camino de Santiago, (newsletter) with the aim of encouraging the creation of associations for the care and promotion of the Pilgrim’s Way. He devoted a great deal of energy to the project of bringing together scholars, pilgrims, clergy, politicians and intellectuals, a project that took shape in the First International Pilgrim’s Way Conference held in Jaca in 1987.

A few months later, the Council of Europe declared the Camino de Santiago the First European Cultural Route. In 1993 it was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.